The Dangers of Reading Too Much (Part 1)

Does excessive reading exacerbate autism and other psychiatric diagnoses?

“Neither Christ nor Buddha nor Socrates wrote a book, for to do so is to exchange life for a logical process.”

—William Butler Yeats

As a kid, I loved to read. In elementary school, I frequently spent recess and lunch in the back of the library, nose buried between the pages of a novel. I convinced my mom to leave me in the local kids’ bookstore or the library while she ran errands. My Brownies troupe gave me the award for “most likely to be found in the bunks reading” at the end of one of our outdoor camps. I devoured books well above my comprehension level in days, including Margaret George’s The Memoirs of Cleopatra the summer before grade four, and The Hunchback of Notre Dame and A Tale of Two Cities before I started grade six.

I was a hardcore lover of science fiction and fantasy series and a collector of comics anthologies. After high school, I got a BA, then an MFA, in creative writing. I volunteered, then worked, at a literary journal for nearly a decade. I over-identified with the bookish Susie Derkins from the comic strip Calvin & Hobbes, so much so that I used her name as my handle on OKCupid as recently as 2020. Because I hate jewelry, when my now-husband proposed my engagement gift was all sixty-four Animorphs books, my favourite series as a kid.

The benefits of reading—even reading excessively—are widely touted. Reading increases empathy, improves intelligence, and “makes you a better person” according to dozens, perhaps hundreds, of articles. How can it be possible to “read too much”? How can reading, that most lauded of solo activities, be dangerous?

Ironically, I slowly arrived at this conclusion the only way I knew how; by reading, reading, reading, way too much.

At the beginning of 2019, while in a mental health spiral that would culminate in a psychological breakdown at the start of the Covid-19 pandemic, I switched my obsessive reading from fiction and poetry to non-fiction. I was trying to understand what was wrong with me, with my family, and with the consumerist, greed-focussed, attention-driven, and alienating culture around me.

I dove headfirst into literature on psychology, human biology, Western history, and economics. I became obsessed with epigenetics and endocrinology, and with the literature on both narcissistic personality disorder and autism. My early research, done primarily via audiobook while chain-smoking marijuana and climbing the Tetris Effect and SuperHyperCube leaderboards, would result in my first published essay, which appeared in The Walrus in October 2019 and promptly went viral. Encouraged by this reaction, I continued to research—and write—in earnest.

Then in early 2020, just before the Covid lockdowns, I stumbled upon the first of three science writers who would inspire many of the ideas to be shared in this blog.

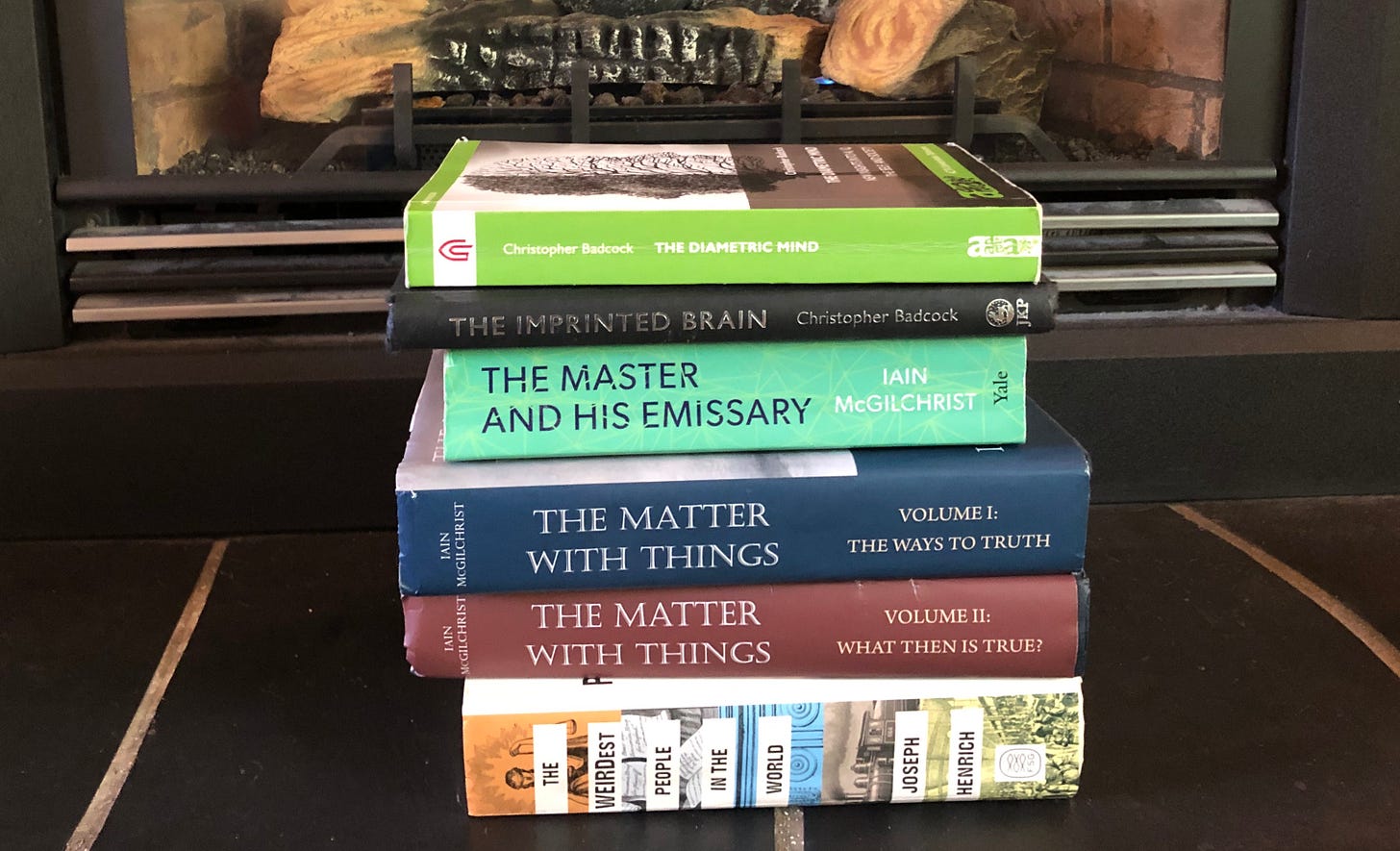

Christopher Badcock, a sociologist from the London School of Economics, has written two obscure books and a Psychology Today column about his controversial “imprinted brain” theory. Badcock and his research partner Bernard Crespi, an evolutionary biologist from Simon Fraser University, posit that there are two types of cognition—mechanistic and mentalistic—and that autism and schizophrenia are diametrical disorders of mentalism (hypo-mentalism and hyper-mentalism respectively). There is a tug-of-war between maternal and paternal genes during gestation, they argue, with over-expression of paternal genes resulting in autistic traits and maternal genes schizoaffective ones. Their intriguing paper, “Psychosis and autism as diametrical disorders of the social brain”, appeared in Behavioral and Brain Sciences in 2008, followed by Badcock’s first book on the topic, The Imprinted Brain: How Genes Set the Balance Between Autism and Psychosis, in 2009.

There are several criticisms of Badcock’s hypothesis, notably that his description of schizophrenia is inaccurate, and he does not adequately account for why autism and schizophrenia so frequently co-occur in the same individuals. Badcock dismisses the latter claim by explaining that autism develops in childhood and schizophrenia in adulthood in these cases, who go from “hypo-mentalistic” to “hyper-mentalistic” with age and are often geniuses. He provides Isaac Newton, Beethoven, and mathematician John Nash as examples.

Despite these issues, and other flaws I’ve noticed in his work, I find Badcock’s ideas compelling, in particular his speculations about the “Western” mind. Providing multiple examples from the canon of literature, philosophy, and psychology, he explains that the West has become increasingly “mechanistic” and “autistic” over the past few centuries, at the expense of “mentalistic” cognition.

According to Badcock, the West is not only hypo-mentalistic, but anti-mentalistic—an observation that will likely resonate with anyone frustrated by the reductionist, mechanistic nature of Western philosophies, science, and medicine. In his 2019 follow-up, The Diametric Mind: New Insights into AI, IQ, the Self, and Society, Badcock suggests the West is currently living in “The Age of Asperger.”

Around the same time as the publication of The Imprinted Brain, two other researchers published works with theories that bore remarkable similarities to Badcock’s observations about the “Western” mind. In 2009, Dr. Iain McGilchrist, a psychiatrist and literary scholar from Oxford University, published The Master and His Emissary: The Divided Brain and the Making of the Western World, a 600-page tome on the differences between the left and right hemispheres of the brain. While McGilchrist’s theory is fundamentally different than Badcock’s, they share the observation that the “Western” mind has become lopsided over the past 500 or so years, in the case of McGilchrist’s conception, in favour of the left hemisphere at the expense of the right.

McGilchrist explains that while both hemispheres are active for everything we do, each hemisphere is dominant in different areas (and inhibits the other) and each understands and interacts with the world in different ways. The right hemisphere is the dominant processor of our relationships to our embodied selves, to nature, to food, to spirituality, and to other people and all living things. The right hemisphere is also dominant in processing music and nonverbal communication. The left hemisphere, on the other hand, contains the language centres of the brain, and is dominant when we interact with non-living things, such as machines. The left hemisphere is abstract, reductionist, uses bottom-up processing, emphasizes logic, order, rationality, and bureaucracy, and understands things in black-and-white. The right hemisphere is holistic, uses top-down processing, emphasizes change, empathy, and openness, and is the hemisphere of the brain responsible for meaning-making. The left sees things, including our own bodies, as an assemblage of parts, whereas the right sees the complex and systemic whole. The left is narcissistic, while the right is relational. The left hemisphere apprehends, while the right comprehends. The left explains, while the right understands.

From The Master and His Emissary (page 93):

“I believe the essential difference between the right hemisphere and the left hemisphere is that the right hemisphere pays attention to the Other, whatever it is that exists apart from ourselves, with which it sees itself in profound relation. It is deeply attracted to, and given life by, the relationship, the betweenness, that exists with this Other. By contrast, the left hemisphere pays attention to the virtual world that it has created, which is self-consistent, but self-contained, ultimately disconnected from the Other, making it powerful, but ultimately only able to operate on, and to know, itself.”

In the second half of The Master and His Emissary, McGilchrist dives into the Western canon of literature, philosophy, and art, pulling from disparate sources to demonstrate how Western thought has become increasingly left-hemisphere dominant since the end of the Renaissance era, and in particular following the Industrial Revolution of the late 1700s and early 1800s. He notes the rise in psychological ailments associated with deficits and/or dysfunction of the right hemisphere—of disruption in our relationships to others, to nature, to food, and to our own bodies—including autism, schizophrenia, eating disorders and body dysmorphia, anxiety disorders, and various personality disorders including borderline personality disorder and narcissism.

McGilchrist published a follow-up, The Matter with Things: Our Brains, Our Delusions, and the Unmaking of the World, in 2021. In a 2023 interview with Unherd magazine, pointedly titled “Left-brain thinking will destroy civilization”, he says:

“It’s not that we’ve all got schizophrenia — of course we haven’t — but what I think is that we’re all neglecting the right hemisphere. Schizophrenia is a case in which the left hemisphere has gone into overdrive, and the right hemisphere has been wound down or is not really being listened to, and this leads to delusions and hallucinations. I think we are now in a world which is fully deluded. We’re all fairly reasonable people, but now it’s quite common to hear people say — and for them to go completely unchallenged — things that everybody knows are completely impossible. They don’t have any science behind them. There are aspects of our culture that have become very vociferous and very irrational, and very dogmatic and very hubristic. “This is right, and anyone who says otherwise is wrong.” That’s the way the left hemisphere likes to be. Cut and dried, black and white. But the right hemisphere sees nuances, gradation: there’s good and bad in almost everything.”

In another interview, he argues, like Badcock, that Western society is becoming more “autistic” too.

Finally, a third researcher, Joseph Henrich, currently of Harvard, published his landmark paper “The weirdest people in the world?” in 2010 while a professor of psychology and economics at the University of British Columbia. Henrich’s work is probably the best-known of the three men; his paper has been cited over 11,000 times and was expanded into a widely-reviewed book The WEIRDest People in the World (2020). The acronym he and his co-authors coined, “WEIRD” (Western, Educated, Industrialized, Rich, and Democratic), has entered common usage in the psychology and human biology communities. Henrich’s core argument is the simplest and most obviously true of the three: that behavioural science research is inherently flawed because the vast majority (approximately 96%) of study participants are drawn from Western industrialized countries (Europe, North America, Australia, and Israel), including 68% from the United States. Furthermore, even within the West, samples are not representative, as the majority of participants—67% in the US and 80% in other countries—are drawn from undergraduate psychology courses. “In other words,” the authors write, “a randomly selected American undergraduate is more than 4,000 times more likely to be a research participant than is a randomly selected person from outside of the West.” These studies are then problematically used to make generalizations about all of the human species.

The problem compounds because WEIRD people are, well, weird. In their paper, Henrich and his coauthors note that “comparative projects involving visual illusions, social motivations (fairness), folkbiological cognition, and spatial cognition all show industrialized populations as outliers.” Henrich elaborates on this in his book, which was published in 2020. While his subtitle—How the West Became Psychologically Peculiar and Particularly Prosperous—understandably rubs many people the wrong way, Henrich does acknowledge the horrors of the Trans-Atlantic slave trade and colonialism and clarifies that he is only saying that WEIRD people are different (on average), neither superior nor inferior. Badcock and McGilchrist, on the other hand, make it clear in their writing that they consider the West’s anti-mentalism / right-hemisphere deficits to be a bad thing for humanity, with McGilchrist going as far as to predict in the final chapter of The Master and His Emissary a gloomy if not doomed future if something doesn’t change.

Intriguingly, having read the work of all three writers, while they largely draw on the same bank of research to support their respective ideas, I spotted no evidence that any of them were aware of each other when they first published their theories.

A couple of years ago, a friend told me about a conversation she’d had with her bookish younger sister. Her sister described having an incessant inner monologue, something my friend does not experience (while she has an inner monologue—nearly all of us do—hers has no problem shutting up). I thought this was funny because I have the same problem; the voice inside my head just keeps rambling and narrating and is nearly impossible to silence. Her sister, like me, struggles with anxiety and symptoms of ADHD, whereas my more extroverted friend does not. I threw out a theory—if you spend a significant portion of your developing years with your nose in books, it should come as no surprise if your brain grows up to think like one.

One of the commonalities in Badcock’s, Henrich’s, and McGilchrist’s works is that a key factor they attribute the changes in the “Western” / “WEIRD” mind to is increased literacy following the invention of the printing press by German goldsmith Johannes Gutenberg in 1436. The rise in literacy and decline of oral traditions resulted in cognitive—and epigenetic—changes over multiple generations.

As Henrich discusses in the prelude of The WEIRDest People in the World (pages 6-7):

“[…] highly literate societies are relatively new, and quite distinct from most societies that have ever existed. This means that modern populations are neurologically and psychologically different from those found in societies throughout history and back into our evolutionary past […]

[…] Suddenly, in the 16th century, literacy began spreading epidemically across western Europe. By around 1750, having surged past more cosmopolitan places in Italy and France, the Netherlands, Britain, Sweden, and Germany developed the most literate societies in the world […] remember that underneath this diffusion are psychological and neurological changes in people’s brains: verbal memories are expanding, face processing is shifting right, and corpus callosa are thickening—in the aggregate—over centuries.”

Reading and writing use both brain hemispheres—as does everything we do—but they are typically left hemisphere dominant tasks. In-person communication, on the other hand, activates more of the right hemisphere, which processes facial expressions, body language, and tone of voice. It can be inferred that as people spend more time engaging with the written word instead of with each other, they become more left-hemisphere dominant. As well, because speech is mostly a left-hemisphere task, talking via phone or video call would similarly favour the left hemisphere more than in-person communication.

Badcock argues that reading is inherently “mechanistic” and that literacy is “‘autistic’ to the extent that it not only mimics the autistic savant’s ready recall of words verbatim or facts with perfect precisions, but allows private, personal access to another person’s thoughts without having to interact with that person in a social context.” (The Diametric Mind, page 290).

“In compensating for their inevitable mentalistic deficits, written texts might not simply try to achieve the same result by different, conscious, more round-about means just as intelligent autistics do, they might also promote a more “autistic,” mechanistic way of thinking as an alternative to the mentalism they fail to reproduce.” (The Diametric Mind, page 288).

While Badcock, McGilchrist, and Henrich look at how the printing press and literacy affected the Western “mind” on a cultural and societal level, after reading their arguments and reflecting on my bookworm-y childhood, I began to wonder how excessive reading, especially during childhood during the critical years of brain development, affects us at an individual level. Did I exacerbate my own mental health struggles and ADHD/autistic traits by spending too much time with my nose in novels? Is the never-ending inner narrator that so often plagues me a natural consequence of excessive reading in childhood?

I’m not coming after books here. Reading books—good ones—is certainly good for the mind in moderation. And audiobooks, in theory, would activate the hemispheres more equally than print. I’m still pro-book.

But by reading I mean the act of interpreting text from a screen or page, including text messages, emails, social media comments, news articles, and blog posts. While excessive reading of books is unhealthy and probably makes a person more “autistic”, this was always relatively rare. In contrast, screens are everywhere and a lot more people are addicted to their phones than to books.

Back in 2015, Iain McGilchrist tried to sound the alarm about smartphones making younger generations “borderline autistic.” His concerns were largely dismissed, and criticized by neurodiversity activists (they attack anyone who dares suggest autism can be caused by anything other than genetics). The counter-arguments to McGilchrist’s claims rest largely on the fact that autism is typically diagnosed before children are given smartphones, and that rates of diagnosis were rising for decades before their invention.

The problem with these criticisms is that McGilchrist never claimed smartphones were the only cause of autism, just that excessive time spent on them would exacerbate traits associated with the condition. In The Matter with Things, McGilchrist claims that autism is “not a unitary condition” (page 307), and that while “there may be a virtually infinite number of causes of a complex system’s malfunctioning, there are only so many ways in which that malfunctioning can manifest itself.” (page 325). In other words, smartphones are a potential cause of the rising rates of autism diagnoses, but not the cause. The black-and-white thinking of McGilchrist’s critics is ironically an example of the left hemisphere dominance and right hemisphere dysfunction he is warning us about in his books.

Text is now the primary way many if not most young people communicate with their friends. As I discussed in my introductory post (“Particles and Waves: On Changing Your Mind”), this communication-by-particles has negative impacts on both our mirror neurons (which don’t work properly over screens and especially if you can’t see or hear the person you’re “talking” to at all) and oxytocin levels (causing spikes and crashes). Our left hemisphere becomes more active and dominant, while our right becomes dysfunctional. We become more mechanistic, more “WEIRD.”

From this, it’s reasonable to conclude that the skyrocketing rates of both adults and children seeking diagnoses of “ADHD” and “autism” over the past three years are largely a result of “autistic” traits, attention problems, and general anxiety being exacerbated by the rise in screen time—and time spent alone in general—during the Covid years (please note my word choices in italics before sending me an angry reply).

This is further complicated by the fact that the left hemisphere is gullible, whereas the right hemisphere is our lie detector.

From The Master and His Emissary (pg 71):

“ … the left hemisphere does not attend to the eyes: this is one reason why the right hemisphere picks up subtle clues and meanings, and because it can understand how others are feeling and thinking, we rely on it when we judge whether people are lying. Those with right hemisphere damage have difficulty distinguishing jokes from lies, by contrast those with left hemisphere damage are actually better at detecting a lie than normal individuals …”

This suggests that we are more likely to uncritically believe ideas and information that we read over what we are told in person. Without access to information processed in the right hemisphere, such as body language, facial expression, and tone of voice, we are forced to rely on “autistic” techniques to detect lies and misinformation in what we read (e.g. logic, pattern recognition) instead of instinct or “gut” feelings. This has tremendous implications in our era of online-driven “fake news”, propaganda, cult-like ideologies, and bad actors.

I’m not calling for anyone to burn their personal library or toss their cell phone in the ocean, but I am saying that for a lot of us, our brains and bodies would thank us if we put down the screens and/or books more often and instead spent time talking to others in person, walking in nature, meditating and doing yoga, and dancing on the beach.

This concludes Part 1 of “The Dangers of Reading Too Much.” Part 2 will be published next Sunday.

This is very inconsistent with my personal experience with Asperger's. I was diagnosed as a teen back when it was still a diagnosis that was given in the US, and as an adult I feel the diagnosis describes me very well.

First, the verbosity you describe as being typical of autism is, well, not. It is true that a lot of type 1 autistics or aspies are hyperlexic. But a lot of us think more in images and nebulous concepts--famously, Temple Grandin. Non-famously, me; and I have been a tremendous bookworm both as a child and at present. I have little to no internal monologue unless I exert conscious effort to put my thoughts into words. Beyond that, type 2 and type 3 autistics commonly have difficulties with language and speech, to the point of being selectively or entirely nonverbal.

Second, re: detecting lies. Most people vastly overestimate their ability to identify when someone is lying. On average, trying to tell when someone is lying doesn't give you any more accurate information than flipping a coin. (Secondary source: the American Psychological Association, here: https://www.apa.org/monitor/2016/03/deception) I find it laughable when someone suggests that I should rely more on gut instinct and nonverbal cues than on factual context and theory of mind to identify whether someone is being motivated to lie to me.

Third, as an aspie, reading fiction helped me develop better theory of mind, and helped me develop skills to better relate to other people. Obviously real people don't function quite like book characters, but trying to tease out the intentions and motivations of fictional characters was good low-stakes practice for interpreting the more complexee, nuance, and consequential information I come across in real life.

Finally--something i do agree with you on. The digital age, and digital entertainment, certainly do distance us from out direct experience of our bodies. It would not surprise me if the average teen today had less kinesthetic awareness and worse vestibular & proprioception processing (common traits of autistic people!) than a teen in, say, the 60s. Put more broadly, I do think it's plausible that being extremely bookish exacerbates the motor problems associated with ASD. For that reason we could all do with some more yoga or team sports or whatever activity catches one's interest.

Interesting stuff that dovetailed with McGilchrist!

But the main cause of autism is aluminum. Dr Christopher Exley examined brains from a bank that died of autism and Alzheimer's... It's a 90+% correlation in both!

https://drchristopherexley.substack.com/

I can say that I don't have the super chatty mind but I was very much into books! I used to read everything I could get my hands on. But that wasn't forced until school where teachers expected us to read Shakespeare and be experts at it.... Or to memorize what year so and so signed a treaty.... Or math and science classes that made us memorize formulas....

That's where the damage kicks in. I dropped out of college in favor of a technical field. I couldn't keep memorizing shit. It went against my being. And haha, later on I meet these engineers who can't even remember basic formulas 😂.

Here's a quote that gives a funny point about higher education:

"The evolutionary psychologist William von Hippel found that humans use large parts of thinking power to navigate social world rather than perform independent analysis and decision making. For most people it is the mechanism that, in case of doubt, will prevent one from thinking what is right if, in return, it endangers one’s social status. This phenomenon occurs more strongly the higher a person’s social status. Another factor is that the more educated and more theoretically intelligent a person is, the more their brain is adept at selling them the biggest nonsense as a reasonable idea, as long as it elevates their social status. The upper educated class tends to be more inclined than ordinary people to chase some intellectual boondoggle. "

-Sasha Latypova